Barrick subsidiaries in UK court this week for previous rights abuses at its North Mara mine

Download full press release and briefing here.

Update (23 March 2022): For RAID’s complaint to the LBMA see here.

“Barrick’s claims that it has tackled human rights abuses at the North Mara mine just don’t stack up. The shootings and beatings by Tanzanian police assigned to the mine are a world away from Barrick’s rosy sustainability reports and partial assessments. Barrick’s board and investors should ensure an end to the mine’s relationship with the police and set up a truly credible and independent investigation into the abuses.”

– Anneke Van Woudenberg, Executive Director at RAID

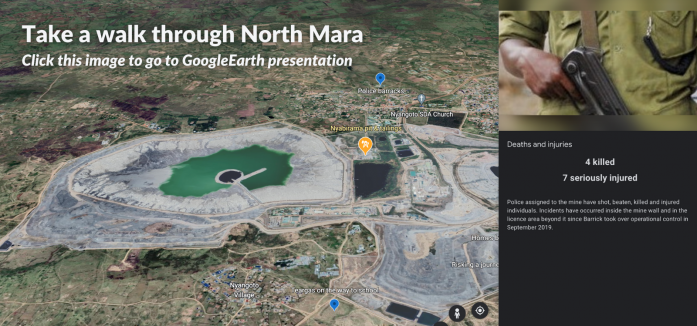

At least four people have been killed and seven more seriously injured by police engaged to provide security at Tanzania’s North Mara Gold Mine since Barrick Gold assumed control of the mine in September 2019, UK corporate watchdog RAID said today. The alarming human rights abuses shatter the Canadian mining giant’s claim that it has “radically repaired” community relations at the mine, after taking back operational control from its UK subsidiary, Acacia Mining.

Barrick subsidiaries are due in a British court on 17 March to face allegations of unlawful killings and assaults at the mine between 2014 and 2019. The claimants include the family of a nine-year-old girl killed by a mine vehicle driven by police, and four women who were fired upon while gathering around her body. Barrick’s subsidiaries deny liability.

RAID has conducted six research missions to North Mara and interviewed more than 90 people over the past 28 months, following up on reports that the human rights situation remained of serious concern. RAID’s team interviewed those injured, their families, witnesses, local authorities, village leaders, police officers, security personnel and former mine employees, who provided credible information about new killings and assaults by Tanzanian police assigned to the mine, identified by local residents as “mine police”. The vast majority of the human rights incidents occurred in the past 12 months.

According to witnesses, three of those killed were attempting to leave, or had been chased from, the mine site. Two were shot with live ammunition while the third was struck with a large projectile, possibly a teargas canister or sound bomb, in the back of his head. RAID found no evidence that the force used by police was proportionate or necessary.

Officers identified as mine police were also reported to beat local residents. In one case, police broke into the home of a local resident, Joseph (not his real name), who they accused of being an “intruder”. According to Joseph, police who guard the mine dragged him into the yard saying, “This is one of those who are giving us problems.” They hit him repeatedly on the head, kicked and beat him.

Local leaders and residents deplored the actions by the “mine police” who they said regularly invade residential areas, force their way into homes without a warrant, arbitrarily arrest and beat residents, and fire teargas and ammunition indiscriminately, including near children. Police guarding the mine are described as being armed with rifles, submachine guns, batons, teargas launchers and sound bombs. According to a village chairman, “The mine police… always look like they’re going to war.”

In one incident in January 2022, police guarding the mine fired teargas near children on their way to school. A grandmother who was passing nearby told RAID she heard the teargas discharge and saw the smoke. “I heard the cries of the children who were going to school. I felt so bad, but I wasn’t in a position to help, and some of the children started to choke.” She said the “mine police” laughed at the crying children, telling them “we brought you corona [Covid-19] medicine.” RAID researchers found remnants of multiple teargas canisters near homes around the mine.

In reply to RAID’s request for information on the reports of recent killings and assaults, Barrick said, “it would not be appropriate to discuss any allegations raised by RAID outside of the English High Court proceedings”, though RAID is not a party and the allegations do not concern incidents subject to those proceedings.

Mine vehicle used by police deployed at Barrick’s North Mara gold mine ©2022 RAID

The mine’s relationship with the police

The mine has a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Tanzanian police, under which an estimated 100 to 150 police are assigned to provide security at the mine. They include both regular officers and members of Tanzania’s Field Force Unit, a specialist division responsible for riot control. The mine pays, feeds, accommodates and equips them. In response to the allegations, Barrick said that references to “Mine Police” are “factually incorrect”, and that the mine does not employ, “supervise, direct or control” police assigned to it, and is not responsible for their conduct.

However, nine members of the mine’s internal security team and the police interviewed by RAID, described how police assigned to the mine were part of the mine’s security structure and were overseen by its security team. They said police are present in the mine’s security control room where security operations are monitored and directed; are deployed to specific areas around the mine site; use the same radio frequency as the mine’s security team; and regularly bring individuals arrested at the mine site to be photographed and processed by the mine before being taken away, raising concerns regarding the rights of detainees.

Former members of the mine’s internal security team raised concerns about the mine’s relationship with the police. Those interviewed by RAID said the mine’s extensive use of the police increased security risks due to the police’s persistent unlawful conduct. One said, “to be honest, the police are a nightmare. How can you have a situation where the people who are meant to uphold the law are the worst example of breaking the law?”

RAID has repeatedly raised concerns about the behaviour of the police assigned to the mine, urging Barrick and its subsidiaries to consider ending the company’s reliance on the police for its security needs.

Barrick said that it “seeks to avoid causing or contributing to human rights violations,” that the human rights concerns at the mine are “legacy issues” and that the relationship with the Tanzanian police was reviewed “to establish clear boundaries” since bringing the North Mara mine back under its control. It says third party human rights assessments conducted at the mine since 2019, the most recent in early 2022, found “considerable improvement…[on] security matters at the mine since Barrick took over operational control.”

“Unpublished assessments conducted at the mine have been commissioned or largely influenced by Barrick, so it’s no surprise they are at odds with distressing accounts from local residents,” said Van Woudenberg. “Whatever recent ‘boundaries’ Barrick may say it has in place with the police does not alter the fact that the company continues to engage, pay and equip abusive and unaccountable police to guard its mine.”

Click to view presentation here (and then click “present”)

For more information, please see:

- To read Barrick’s full response to RAID, please click here

- A RAID press release on the UK legal action against Barrick subsidiaries, and addition of claims

- A RAID press release on its previous submission to the LBMA concerning the North Mara Mine

- A RAID editorial about key problems for Mark Bristow’s as he takes the reigns of Barrick Gold

Update: On 14 March, Barrick published a statement in response to RAID’s publication. RAID issued a rebuttal which can be found here.

Police Violence at the North Mara Mine

Barrick is one of the world’s largest gold miners with revenue of nearly $12 billion in 2021. It says it plans to include the North Mara mine, in northwestern Tanzania, in its elite “tier one” portfolio.

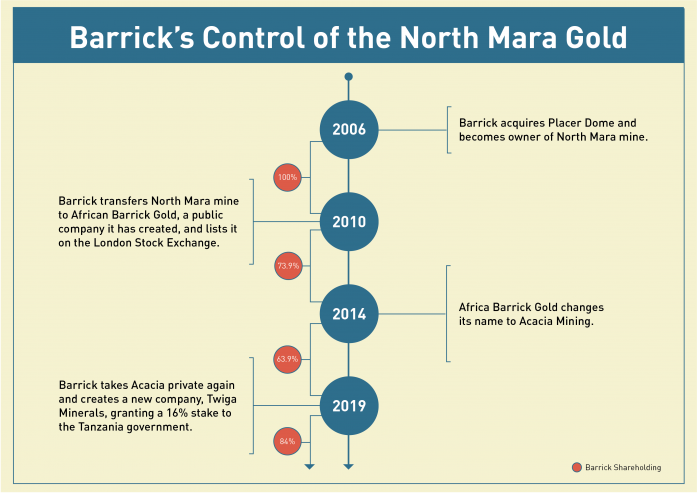

Barrick acquired the North Mara mine in 2006, owned through Barrick’s local subsidiary, North Mara Gold Mine Limited. From 2010, the mine was operated by Barrick’s subsidiary, African Barrick Gold, which it listed on the London Stock Exchange, retaining a controlling financial interest. In 2014, African Barrick Gold was renamed Acacia Mining. In September 2019, Barrick bought out Acacia Mining’s minority shareholders, delisted it and took it back in-house. It now operates its Tanzanian mines, including North Mara, through a newly formed company, Twiga Minerals, in which the Tanzanian government holds a 16% stake. Throughout these changes, Barrick’s shareholding has not fallen below 63.9% and it was more often higher.

A legacy of human rights abuses

The latest incidents that RAID has documented in this briefing follow over a decade of reports of serious human rights violations at the North Mara mine. Since commercial industrial mining began at North Mara, there have been credible reports of 75 people killed and 287 people injured by police responsible for mine security (including the reports received in person by a Tanzania Parliamentary inquiry in 2016). Local leaders involved in the inquiry told RAID they believed this was an underestimate. RAID is not aware of a single police officer having been brought to justice for any crimes committed in relation to these incidents.

RAID interviews

The interviews referenced in this briefing were all conducted by RAID after Barrick took operational control of the mine in September 2019. Nearly all of those interviewed by RAID spoke on condition of anonymity due to concerns for their safety or circumstances of employment, which RAID assessed were reasonably held. Accordingly, all names have been changed and care has been taken to protect identities.

Recent killings of local residents

RAID documented four killings since Barrick took operational control of the North Mara mine, the earliest of which occurred in December 2019. Those killed ranged in age from 22 to 29, and three were fathers to young children.

According to witnesses and family members interviewed by RAID, three were shot by police guarding the mine while fleeing: two were shot with live ammunition, and the third with a large projectile that struck the individual in the back of the head. The fourth person died after being injured by police officers on a road regularly used by local residents that runs by the mine wall.

RAID found no evidence that the force used by police was proportionate or necessary, as mandated by international standards. On the contrary, the evidence gathered indicated that it was neither proportionate nor necessary.

For instance, in the case of Thomas (not his real name), a witness told RAID that Thomas and others had gone to search for gold-bearing material in an area where the mine dumps waste rock. When police arrived, the group was ordered to leave. According to the witness, as they were leaving:

“I heard about three rounds of shots. One of them must have hit [Thomas] because I heard him cry out for help. I was ahead of him by about ten metres and when I turned around, I saw him on the ground.”

A second witness corroborated this account. A member of Thomas’ family later told RAID that a doctor at the local mortuary confirmed that Thomas had been shot through his midriff.

In another case, a witness told RAID that he and Peter (not his real name) had also gone to a waste rock area on the mine. When the police came, they “said some derogatory words, like these f*****s [homophobic term] are here…. When the police started shooting, we ran”.

He and Peter fled with others from the mine site to a nearby residential area, with the police in pursuit. The witness recalled that as they entered the residential area, the police opened fire. “We were close to one another,” he said. “[Peter] was just behind me. If the bullet hadn’t hit him, it might have hit me instead.”

Peter’s mother told RAID that a doctor had confirmed that her son had been shot after his family found his body at the local mortuary. When asked if she had reported the incident to the mine, she replied, “Why would I go to the mine? The police just kill people and then go back there.”

Daily journeys take people along the mine wall at North Mara ©2022 RAID

Recent assaults of local residents

The recent assaults documented by RAID all occurred in the last 12 months. Three of the injuries were caused by shootings, two by severe beatings, and two by the ramming of a mine vehicle driven by police into a motorcycle, injuring a young man and woman who were on their way to work. Multiple witnesses independently said that it appeared the mine vehicle crossed the road to strike the motorcycle.

Some of the injuries are likely to be life-changing. RAID found no evidence that the force used was proportionate or necessary in any of the assaults.

In one case, John (not his real name) had gone with several others to a waste rock area, until security personnel arrived and told them to leave. As the group was exiting the mine site, the police gave chase. John said that he had made it to the outskirts of an adjacent village when he heard gunshots and “felt like I had been hit by a nail… I looked down at my leg and saw dust, but immediately after I realised that I had been shot.”

John said he tried to continue running, but the “pain became too unbearable, and my leg started getting numb”. A friend came to his aid and “had to carry me on his back.” A witness later confirmed John’s account.

Patrick (not his real name) was on a road by the mine wall when he was caught up in a mine security operation and shot in the stomach by police guarding the mine. In another case, George (not his real name) was coming home from work on a motorcycle along a route that took him near the mine when police opened fire, with the bullet entering one side and exiting the other around his hip. Neither was provided with assistance by police or mine personnel, and both suffered serious injuries. Walking remains difficult for Patrick, and George’s family was told that he may permanently lose the normal use of one leg without medical treatment, and that his reproductive system may also have been damaged. The family said that they cannot afford the required tests or medical treatment. George is in his mid-20s and had just married.

Two of those who were injured were beaten severely by multiple police officers. In one case, Emmanuel (not his real name) was seized by police, who had chased him from a waste rock area. He recalled that there were a lot police, and that:

“Some of them started beating me up. They beat me really bad. They were using heavy batons [and] the butt of the gun to hit me on the head, on the joints, and they had pangas [machete-like tools used for agriculture] as well, and were using the side to hit me on the head.”

He said that they beat him until he was disoriented and “wasn’t speaking coherently”, and gouged his leg, opening a large, deep gash.

The other beating occurred after police broke into the home of Joseph (not his real name), accusing him of being an intruder (see above). He told RAID:

“The police told me that they went to my home because I was an intruder running away from them. I was telling the police, I was at my home, you’ve already heard me tell you this. They didn’t have a warrant, they didn’t show me any papers or anything like that. They never have any documents, they just go around hurting people.”

He locked himself in his home, but said that they broke down the door and dragged him into the yard, recalling:

“The moment they pulled me out, they started attacking me, beating me, kicking me. My wife began crying and asking them to stop, but one of the policemen said he would shoot her if she didn’t shut up. Other people came and also asked them to stop, they were asking the police, ‘are you here to protect the people or to work for the mine?’ The police were saying that these are the people who disturb us at night, why do you always disturb us.

I was saved by the people. When more people came, that’s when the police finally stopped. The beating took maybe 15 minutes. They were taking turns, they would leave me and then another would come.”

Joseph said that the police left without arresting him or assisting him to get medical treatment. He told RAID, “I got sick for a very long time after that. In my right ear, I still can’t hear properly, and if I try to open my mouth, I still feel pain. I still get headaches.” He said he had not been able to afford medical care. “It’s just financial challenges,” he explained. “My work just gives me enough for my family. Even the door that they broke, it took about one week to fix.”

Police with mine vehicle deployed by homes watch over Barrick’s North Mara mine ©2022 RAID

Identification of the police

In respect of each of the killings and injuries documented, witnesses and those injured confirmed that the police involved were “mine police”, as local residents and leaders refer to police engaged by the mine.

According to those interviewed by RAID, it was mine police involved in the incidents, including because: (i) of where the police had been stationed (for instance, by the mine wall where such police are regularly posted); (ii) they had been in mine vehicles, identifiable, for example, by their license plate, hard top, and wire mesh over windows; (iii) they were in, or had emerged from, the mine site during the relevant security operation; and/or (iv) they were being directed over radio while being tracked by mine security cameras.

Impeding medical assistance

According to international standards, security personnel and law enforcement officials must ensure medical aid is provided to any injured person “at the earliest possible moment”. Yet RAID found that the police involved repeatedly failed to ensure the provision of such aid, and, in some instances, prevented it.

In none of the non-fatal shootings or beatings documented by RAID were those injured provided with first aid, or taken for medical assistance, by the police or mine personnel. Instead, they were either left untreated or detained without access to such assistance.

For instance, Emmanuel told RAID that after he was beaten and seriously injured, the police put him in the back of a mine vehicle for hours without treatment while they continued their security shift guarding the mine. He said:

“I was told to lie down on my stomach, with my arms out. They kept beating me [but] not continuously. They occasionally kicked me in the head. There was a time they had a foot on the back of my neck. I was bleeding a lot, but they didn’t care. I was crying out for water. They had it, but they didn’t give me any. At one point, I was so thirsty, I had to start drinking my own blood. The blood was coming out, it was seeping down my leg…. I put my hand on the inside of my foot, blood would drip onto my hand and then I would put that into my mouth.”

After leaving their shift at the mine many hours later, the police took him to be held in a police cell, also without access to medical treatment. When he was released on bail many days later, he said that the wound on his leg, where police had gouged him, “was going bad. It was getting rotten.”

The mine’s use of the police further inhibits access to medical treatment because victims of assault in Tanzania are generally required to obtain forms, known as PF3 forms, from the police before hospitals will provide treatment. For instance, in one of the recent cases involving a shooting documented by RAID, the hospital would not treat the injured individual without a PF3 form, which the family had to seek from the police. The police refused to provide one, delaying urgently needed medical care.

Moreover, some of those interviewed by RAID said that it was unsafe to seek a PF3 form from the police for incidents in which the police are implicated. The sister of one person who was shot by police guarding the mine told RAID, “We couldn’t get a PF3 because we didn’t want [my brother] to be in police hands. The police have a habit, if they injure someone, then they kill them and then take them to the mortuary.”

While RAID has not found evidence verifying such a practice, the fear that police might deliberately kill those they had injured was expressed by others who RAID interviewed.

In one case, the family of the deceased also described police as directing medical staff as to what to record about the killing, and impeding family members’ efforts to obtain medical documents.

Police in a mine vehicle deployed across the road by Barrick’s North Mara mine ©2022 RAID

Intrusions into residential areas, indiscriminate use of teargas and live ammunition

People in many communities are forced to live in extremely close proximity to the mine. Barrick’s subsidiary, Acacia Mining, admitted in 2019 that it had failed to provide a 200-metre buffer zone between the mine’s perimeter and certain communities, which local leaders told RAID is inconsistent with Tanzanian law. The failure to ensure an adequate buffer appears to persist since Barrick took operational control, with many people’s homes separated from the mine wall by only a narrow dirt road.

Close proximity to the mine site increases risks for local residents and exposes them to security operations and harassment by police guarding the mine. RAID was independently informed by 13 local residents and leaders that these police regularly enter their villages, in some areas multiple times per week. During these security operations, the police force their way into homes without a warrant, arbitrarily arrest and beat residents, and fire teargas and live ammunition in the vicinity of children and the elderly.

A young woman who resides close to the mine told RAID:

“When they are chasing intruders [from the mine site] they just fire live ammunition and teargas in the community, around children, they don’t care…. Our [windows are] only wired, so the gas just comes into the house and the children cry and complain about pain in their eyes.”

Teargas is known to cause burning and choking sensations, respiratory distress, and more serious and longer-term health-related effects. In one case, in January 2022, a woman said that her elderly mother had passed out for several hours from the smoke.

In another incident in February 2022, teargas and live ammunition were fired at and around local shops in Nyabichune village, which is adjacent to the mine. According to local residents interviewed by RAID, one of the bullets struck the side of a shop, while a canister struck a shop door, discharging its contents into a young woman’s face, causing itchiness and rashes. The woman, who said that intrusions from police guarding the mine occur on a weekly basis, told RAID that during the same incident another canister had “ricocheted into another shop and almost hit a woman’s chest. The whole area was filled with smoke.”

A local resident added:

“The police who came were police from the mine.… They were firing bullets in the air and others were firing teargas bombs at people and at buildings. It was very chaotic, like war. I know they were teargas bombs because people were complaining of itchy eyes. The smoke was affecting their eyes, and they were crying out that they couldn’t see…. Children were there, they were running. You can’t tell the depth of psychological damage for children.”

The resident estimated that over a dozen canisters were fired in this one incident, as well as live ammunition. He said that police from the mine “come into our [residential] area firing bullets and bombs often” and that the problem had been “picking up” in frequency. “The police have to know that it is a residential area, where children and pregnant women are around,” he said. “Sometimes women fall because of the impact of what happens. It’s very problematic.”

He said that the matter had been reported to the local police, who in turn had called “the leader of the police who guard the mine”, but they had directed local residents to speak with village leaders to organise a meeting with the mine. He said that residents had reported the issue to the village leadership, but, as in the past, “nothing happens”.

A man herds cows past barracks provided to the police by the North Mara gold mine ©2022 RAID

Local residents and leaders said that police guarding the mine often enter people’s homes. One hamlet chairperson told RAID:

“[The police] go into people’s homes. This happens all the time. These are police from the mine, they are driving mine vehicles. They come to the area randomly. They come into areas where there are children…. It even happens during the day. They don’t care, they only care about the mine, they will just fire anywhere, teargas and live ammunition. They have killed people who were not involved in any incident.”

Asked if the police have warrants when entering people’s homes, the chairperson said, “No, there are no such things, they will just start commanding what they want you to do.”

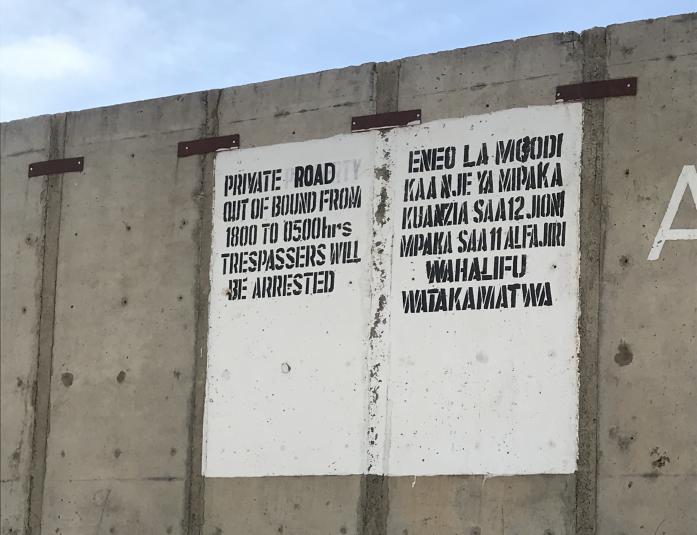

Residents and leaders also told RAID that those caught on a road that runs along the mine wall by Nyabichune village after around 6 pm are regularly beaten, arrested and jailed. They said that there is a “curfew” imposed on their use of the road, where the mine has posted signs stating, “Private road, out of bounds from 1800 to 0500hrs, trespassers will be arrested”. Yet local residents told RAID that, because of their proximity to the mine, it is their main access route, including to and from the village centre.

A local leader told RAID, “People get arrested just for using the road… They could charge you with anything. Most of the time they charge you with armed robbery.” One man who was recently imprisoned for three months after using the road after 6pm, told RAID that he had little choice but to continue using it. “We are basically engulfed by the mine,” he said. “No matter what happens, that is my way home.”

Local leaders told RAID that in previous years they had reported their concerns regarding police guarding the mine conducting operations in their communities and mistreating those using the road, but the mine had either not responded, or otherwise blamed the communities. One village chairperson said, “As local leaders, we wrote letters to the mine complaining about the bad behaviour by the police but the mine has neglected our letters and so we stopped writing [them].” Another hamlet chairperson told RAID that when the issue of mistreatment of those using the road had been raised with the mine on behalf his community, “the mine… said it was our fault for upsetting the police.”

An empty teargas canister collected outside the mine wall near residential area ©2022 RAID

The mine’s oversight of police activities around the mine site

In its response to RAID, Barrick said that, “as with any other private company, North Mara Gold Mine Limited would not be expected to monitor or police the Tanzania Police Force when the Tanzania Police Force undertake their day-to-day policing activities” outside the mine “perimeter”, and “would not always be aware of what policing activities the Tanzania Police Force undertake in the local communities or elsewhere in region for that matter.”

Barrick did not explain how it defines the mine perimeter, but the mine’s property claims extend into residential areas. Barrick also did not explain how this position was consistent with its Human Rights Policy, which states, “We do not tolerate violations of human rights committed by our employees, affiliates, or any third parties acting on our behalf or related to any aspect of one of our operations”, and “In our relationships with host governments… we do our utmost to avoid being complicit in adverse human rights impacts”.

However the mine defines the “perimeter”, security personnel employed at the mine told RAID that the mine does monitor police activities outside the mine walls, including “track[ing] the police all the way through to homes”, and that as mine security, “[i]f you’d witnessed intruders [onto the mine site] going into a house, you’d direct the police there”.

In its 2020 Annual Report to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, a multi-stakeholder initiative of which Barrick is a member, Barrick stated that agreed policing under the mine’s Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Tanzania Police Force includes “areas around” the mine site. A 2016 letter to RAID from the mine also stated that the mine has 444 infrared cameras and 14 FLIR thermal cameras and “continually monitor[s] the security situation in and around the Mine”; it further said that the mine follows up on “any allegation of human rights involving Tanzanian police deployed on or around” the mine (emphases added). It described the monitoring as “consistent with our commitment to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights”.

RAID put these points to Barrick in response to its assertion that the mine would not be expected to monitor activities around the mine by police assigned to it. Barrick, responding through its lawyers, did not address these points, but said that Barrick “is not responsible for the conduct of the Tanzania Police Force”, which is a state body that “operates solely under its own chain of command in accordance with its own regulations”. Barrick’s lawyers further said that neither they nor Barrick “intend to engage in any further correspondence” with RAID.

Stark white boulders placed by Barrick’s North Mara mine mark the plots of those it has displaced ©2022 RAID

The mine’s longstanding relationship with the police

Local leaders told RAID that before the North Mara mine, which began commercial production in 2002, there had been only a limited police presence in the area. Local residents made an income from farming and small-scale gold mining, including in the area now occupied by the mine. An elderly resident who held a prominent local leadership position during that time explained:

“We didn’t have police in the areas around the mine. They only came to the area when the mine came…. It was peaceful. We didn’t have issues like [today]…. Now police go into people’s houses, take people from their houses, sometimes they don’t even take them to the police station or court, they just beat people until they pay them to stop.”

Exploration for what became the North Mara mine began in 1993 by Afrika Mashariki Gold Mines, which was taken over in 1997 by the Australian company, East African Gold Mines. According to local leaders, the mine’s arrival brought significant problems for local residents, including poverty, leading many to go to the mine site in search of gold-bearing material. From the mid-1990s through to the early 2000s, police involvement in the area increased significantly when, according to a detailed complaint by Tanzania’s Lawyers’ Environmental Action Team to the state’s Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance, they carried out forced evictions of local people to clear the area for the mine’s construction.

After Barrick acquired the mine in 2006, the mine’s relationship with the police for mine security was formalised through agreed MoUs.

(a) Police officers assigned to the mine

As noted, an estimated 100 to 150 police officers, including members of Tanzania’s Field Force Unit, a specialist division responsible for riot control, are assigned to the mine under its MoU with the police. They are frequently rotated, generally at least every three months, and are accommodated in nearby barracks provided by the mine, with at least one senior officer accommodated within the mine. According to those interviewed by RAID, most of the police assigned to the mine come from outside the area, though officers from local stations may also be assigned.

Under the mine’s agreement with the police, assigned officers are provided not just with accommodation, but daily payments, meals, vehicles and fuel from the mine. Former mine personnel and local leaders said that the mine also provides one or more senior officers in the region with fuel and vehicle maintenance, which is provided for police vehicles also used during assignments to the mine as well.

RAID was told by former mine employees that police officers assigned to the mine receive 50,000 Tanzanian shillings (c. US$22) per day in addition to their government salary. This additional sum is paid for by the mine. A police officer assigned to the mine since Barrick took operational control told RAID that these additional payments meant his income more than doubled during his assignment. He also told RAID that more senior police officers receive “a lot more”.

On a road by the mine wall, police assigned to the mine enforce a “curfew” on local residents ©2022 RAID

(b) Alignment of the police and mine at the expense of local communities

Local leaders and residents say that these payments and other benefits ensure that the police engaged by the mine are generally aligned with the company at the expense of local communities. As one resident said, “[t]he police from the mine and the mine are just one thing, they are the same.”

Consistent with this view, local residents said they would not take law enforcement matters to police officers assigned to the mine as, according to a former hamlet chairperson, “[t]heir task is to simply protect the mine.” A village chairperson similarly told RAID, “You cannot call the mine police because they would never come to help anyway. They simply never get involved in community issues because their work is to be around the mine.”

A police officer interviewed by RAID assigned to the mine since Barrick took operational control explained his role in similar terms. “I just work for the mine when I am there,” he said. “If an incident occurred in the community that needed the police, it would have to be other police who would go…. We are told that our work is simply to guard the mine. We are only to arrest people who come to the mine.”

When asked about the command structure at the mine, he said that his superior, known as the ‘OC Operations’ (police commanding officer of operations) and assigned to the mine, instructed him and his fellow officers that the mine’s “Security Manager is the top”.

Children on the way to school by the mine wall ©2022 RAID

(c) Police integration within mine security operations

Along with Tanzanian police officers, RAID spoke to six former members of the mine’s security team who regularly participated in security operations with police assigned to the mine. As noted above, they described how the police formed part of the mine’s security structure and were overseen by the mine’s internal security team. They said that police are deployed to specific areas around the mine site; are present in the mine’s security control room where security operations are monitored and directed; and use the same radio frequency as the mine’s security team.

As also noted above, they said that police brought arrestees to mine personnel for processing before taking them away, a practice that was confirmed by local leaders and those RAID interviewed who were arrested or detained at the mine. Asked why the police followed this practice, a former longstanding member of the mine’s internal security team responded, “because the police were doing the mine’s work.”

(d) Concerns about police behaviour raised by the mine’s own security personnel

Yet at the same time, those from the mine’s security team consistently raised concerns about the extent to which the police posed security problems, as well as a danger to local residents, due to police officers’ persistent unlawful conduct. An experienced former member of the mine’s internal security team said of police operations at the mine, “in my personal opinion, it was mafia type gangsterism”.

One reason for the concern was that the tactics used by the police were regarded by the mine’s security personnel as frequently disproportionate and violent. One former member of the internal security team, who had patrolled inside the mine for many years said that the police brought “conflict” and caused “more violence at the mine”. Another longstanding former member of the same team told RAID that “[m]y work would have been way better without the police.” He said, “if the police came, the only result would be injuries or death.”

A second reason was theft by the police from the mine. Former mine security personnel told RAID that police engaged by the mine frequently stole from the mine, including the theft of gold-bearing material. According to an experienced former internal security team member, “the police are the biggest security problem that the mine has.” He described the scale of their theft as “extremely significant”.

One of the ways in which police have sought to enrich themselves has been by bringing local people onto the mine site, or allowing them to enter, in return for payments or a cut of their findings. According to 11 current and former local leaders and former security team members, this illicit practice by the police is well-known and has long been common. RAID was told by former mine security personnel that it includes facilitating access to the mine’s highly valuable, underground areas.

According to an experienced former member of the mine’s internal security team, the team would deploy around 50 to 70 police officers on rotating shifts:

“at key approach routes to the mine, to act as cut-offs. But that just put them in a good place to bring people into the mine. It got worse when the police were redeployed to outside the mine, it was regularly reported back through local sources they would take payment from the ones they allowed or brought in…. you would see police vehicles disappearing into villages, reappearing like 15 minutes later, and you’d know they were picking trespassers up.”

A former member of the mine’s internal security team who patrolled the mine for years told RAID, “The police would take money from people…[and] the police who didn’t get a share would complain.” He also said, “If the intruders got access to a point, we would use a lot of teargas. But intruders would complain, ‘why are you guys doing this when we have paid the police to let us in, and now you are spraying us?’”

Another former member of the same team told RAID:

“The police were just a problem. They made our job harder. They would let people in and then we would be faced with difficulties trying to deal with the people. I saw the police just let people into the mine, they would just walk past the police at the perimeter…. I saw it so many times.”

The security team members said that they reported their concerns up the chain at the mine repeatedly. As far back as 2014, Tanzania’s then Ministry of Energy and Minerals wrote to the mine identifying police “collud[ing] with…intruders” to facilitate access to the mine as an important factor contributing to violence. It directed the mine to cease its heavy use of the police “without delay” so as to achieve, amongst other things, “zero fatalities”. Yet the mine has continued its heavy use of the police.

According to local residents and leaders, as well as mine security personnel, the mine also failed to take steps necessary to prevent the police practice of “colluding with intruders” from continuing. RAID asked Barrick what steps it had taken to address such practice but received no response.

The police’s ability to solicit payments for access to the mine site renders those who do not pay them particularly vulnerable. In the incidents that RAID documented, it found no evidence that any of those injured or killed after going to the mine site had paid the police for access, and there was evidence indicating that the failure to pay may have led to at least some of them being targeted. In Emmanuel’s case (mentioned above), he told RAID that one of the police officers who was beating him said, “We usually let you guys in, but you never pay us. When you get in without doing that, we have to fight you guys so that the white person can know that we are not with you.”

Local people say that dust from the mine’s operations permeates residential areas ©2022 RAID

(e) Police impunity and the absence of a company response

Police operating at the mine appear to do so with effective impunity. Those interviewed by RAID were unaware of any police officer assigned to the mine being subject to discipline or prosecuted for the use of excessive force against individuals. The response of a police officer who had served several rotations at the mine was typical: “I don’t know of any officer getting into trouble for using force.”

RAID asked Barrick if it was aware of any police officers being disciplined or prosecuted for unlawful conduct, but Barrick did not respond.

Former mine security team members told RAID that they repeatedly escalated concerns about police violence and other illegal activities up the company chain, but saw no effective changes. According to an experienced former member of the mine’s internal security team, team members “were constantly reporting what the police were up to, but the mine wasn’t interested. It’s like they didn’t want to know… [It was] very frustrating and demoralising seeing this when you know exactly what’s happening on the ground.”

The former team member also told RAID, “[w]e did what we could, we logged…and reported everything, including human rights violations”, and described Barrick as being “in denial” about the security situation after taking over.

Barrick’s reaction to the alarming human rights situation

(a) The need to address the relationship between the mine and communities

Barrick said that relations with communities were “extremely strained” when it took operational control of the mine in September 2019 but have since been “radically repaired”. It wrote to RAID that the mine is in “[c]ontinuous engagement with the local community” and has “joint initiatives” with local communities and meetings for “sustainable community development”.

Local leaders and residents interviewed by RAID had a different perception of the relationship between the mine and the local community, consistently saying that relations had not improved in their view. A former village chairperson told RAID in the second half of 2021, Barrick “have not brought any changes” for the better. When asked earlier this year by RAID if there had been any changes since Barrick took operational control, an elderly woman from a village adjacent to the mine replied:

“There are no changes since Barrick took over in 2019. Haven’t there been deaths reported recently? Don’t the police disturb communities the same way they used to? What changes are you talking about? Or are you talking about changes in the colour of roofs at the mine? Or changes to their buildings? Come on, there are no changes. Things are still the same.”

In fact, many said that they believed the relationship had deteriorated. As one village chairperson said in the second half of 2021, “In general, I would say the relationship between the mine and the people is not as good as it used to be.” Other local residents and leaders echoed that view, as did former mine employees interviewed by RAID. One told RAID, “the relationship between the community and the mine is bad and has become poorer” since Barrick took operational control in 2019.

Various reasons were given for such views, including decreased community engagement, but the most common reason given concerned Barrick’s closer ties with the Tanzanian government, an issue that is addressed further below. A former village chairperson, for instance, told RAID earlier this year, “Barrick is pushing everything to the government, maybe because now the government has shares in the mine” through their joint venture, Twiga, rather than assuming responsibility for matters relating to its impact on communities.

(b) The need to address the relationship between the mine and police

In its 2020 Sustainability Report, Barrick said that the relationship with the Tanzanian police was reviewed “to establish clear boundaries”. Barrick did not specify what “clear boundaries” in the relationship between the mine and police had been established or how any such boundaries were monitored and enforced. Former mine security personnel told RAID that there was no change in the relationship with the police assigned to the mine, and a village chairperson told RAID, “[t]here has not been a change in police behaviour before and after Barrick took over in 2019. Nothing has changed at all.” This view was shared by other local leaders.

RAID asked Barrick to clarify what “clear boundaries” had been established, but Barrick did not respond to RAID’s question. Barrick has previously publicly assured that police “only enter the mine site when requested by senior management”. However similar provision was made under previous versions of the mine’s MoU with the police dating back at least to 2010, and RAID was told by former mine security personnel and police that under those MoUs, the police regularly operated on the mine site, including for periods in joint patrols with internal mine security. RAID sought clarification from Barrick as to how the provision is monitored and enforced, but Barrick did not respond.

UN experts have questioned “whose interest the public forces are defending” when operating under agreements with extractive companies. They urged those companies to make their MoU with state security forces public, as their confidentiality “prevents public scrutiny and accountability”. RAID requested that Barrick make its MoU with the police publicly available, but Barrick has not done so.

In September 2020, Barrick announced it had replaced the international security firm providing security at the mine, which was G4S, with a Tanzanian private security contractor, Nguvu Moja. RAID was told that other security personnel were also replaced. After appointing Nguvu Moja, Barrick announced that it had “substantially reduced” the risk of excessive force being used by private contractors at its mine sites by removing “all weapons”, and later confirmed to RAID in writing that Nguvu Moja personnel are unarmed. Members of the mine security team raised concerns about the professional conduct of the Nguvu Moja guards soon after the appointment. In documents seen by RAID, the security team raised concerns up the chain indicating that Nguvu Moja personnel were unprepared and insufficiently experienced for the security tasks they had been assigned. According to RAID’s information the problem persists.

In the view of an experienced former internal security team member interviewed by RAID, it was “effectively inevitable” that the removal of “soft options” for private or internal security personnel would mean an expanded role in security operations for the police and a corresponding increase in violence. This view of the consequence appears to be supported by the fact that 10 of the 11 killings and assaults by police in mine security operations documented by RAID since Barrick took operational control occurred in the last 12 months.

RAID sought clarification from Barrick as to how it would ensure that disarming its private security units would not result in an expanded role for the police guarding the mine. Barrick did not respond to RAID’s request for clarification.

Barrick’s “Welcome to North Mara” sign on the mine road through Nyamongo ©2022 RAID

(c) Deflecting responsibility

Based on RAID’s research, there is reason to believe that an expanded role for the police is not just likely to expose local residents to greater violence and human rights abuses, but to further limit the prospect of any kind of justice, a concern expressed by local leaders. One former hamlet chairperson said, “The mine employs the police and not [just] security companies because the police can get away with things and never face charges. They wear ‘government jackets’ and live under the ‘government umbrella’.”

A village chairperson gave a similar explanation in a separate interview with RAID:

“The police are needed so that the mine can get away with things. When death occurs, for example, the mine can always deflect the issue to the police and never take responsibility. If a death is caused by a private company, the company can be sued and those responsible would be held to account. It’s different when the police are involved. Things are usually taken lightly and the whole situation can just be swept under the rug.”

That the mine does not have any responsibility for actions by police officers at the mine is precisely the position that Barrick’s subsidiaries have taken in the UK court action, and the one conveyed to RAID by Barrick’s lawyers.

A former employee at the mine confirmed that this was also the position taken at the mine when Barrick took over operational control, telling RAID:

“When Barrick set forth in North Mara, for all the cases dealing with human rights, they told the community to go to the police, because the company has no responsibility…It is hard, because the police are shooting people. You would be arrested and charged with an offence if you went to them.”

(d) Absence of remedy

Consistent with this position, RAID was told that Barrick closed the grievance mechanism established by its former subsidiary Acacia Mining, which accepted claims from those seeking remedy for human rights abuses by police assigned to the mine. RAID was highly critical of Acacia Mining’s mechanism, which rejected 82% of the 163 “security-related” human rights grievances it concluded, on the basis that it did not provide a fair or independent process.

In its communication with RAID, Barrick said it has resolved the majority of the outstanding grievances (though gave no details on the grievances or their resolution) and “work[s] with Clan Elders to resolve grievances”. It also said that it had worked to ensure that a mine community grievance mechanism “is accessible to all community members”, and that “10 grievances were lodged by the community in 2021”, though without specifying what they concerned. Yet those interviewed by RAID, including those who had unresolved grievances within the former grievance mechanism, were unaware of a community grievance mechanism at the mine or how they could access it, though some had tried to initiate complaints or progress ones within the former mechanism. More specifically, RAID found no evidence that any of those harmed in the incidents it documented had received remedies from Barrick or the mine, though in at least some of the cases, the incident had been brought to the mine’s attention.

Barrick’s Human Rights Policy states that “[w]herever we operate, we seek… to facilitate access to remedy” and that “[w]e are committed…to act in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights”, which provide that operational-level grievance mechanisms are to be, among other things, transparent, predictable, and accessible. RAID informed Barrick that those it interviewed in communities, which included village leaders and those seeking remedies, said that they were unaware of a grievance mechanism at the mine, let alone how to access it or how it operates. RAID requested more information about how the modified grievance mechanism works and where it could find information about its operating procedures. Barrick, through its lawyers, responded that the mine has “an effective grievance mechanism” and that “every effort is made to promote and encourage” its use, but did not provide any information about how it works or where information concerning its operation could be found.

(e) Fear of speaking out

RAID received credible reports of other human rights abuses that it was not able to confirm, including because those affected were not willing to be interviewed, which, RAID was told, was due to fear of speaking out about what had occurred. From the perspective of RAID’s engagement with communities at North Mara beginning in 2014, local residents interviewed have been increasingly fearful about speaking out against the mine since Barrick took control in 2019. Along with maintaining the mine’s relationship with the police, Barrick deepened ties with the Government of Tanzania, its partner in the Twiga joint venture, at a time when opposition leaders, UN experts and civil society organisations raised concerns about the state’s “crackdown on civic space”.

A former hamlet chairperson told RAID that this closer relationship has had a chilling effect locally:

“Now people are not supposed to complain about the mine. In fact, we are expected to say positive things about the mine. Even if there are bad things in the area, you are just expected to say positive things. This is because things have drastically changed. We no longer complain about the mine in the media unlike some years back when I used to be a leader in the village.

The relationship between Barrick and the communities has really deteriorated. I honestly think it’s because the government and mine have become one. The government is supposed to be the protector of the people but how can they do that if they are part of what is perceived to be a problem? It’s really difficult for the villagers now because I don’t see voices to stand up for them. They are on their own now.”

RAID asked Barrick what measures it had to ensure local residents could express themselves freely should they be critical of the mine. Barrick said in its response to RAID that “grievants are encouraged to express themselves freely without fear of reprisals” and that it has a third-party ethics hotline for “community members to anonymously report a concern.” No one interviewed by RAID identified this hotline as a means of raising concerns, and Barrick’s latest Human Rights Report states that no community related human rights complaints were lodged on its helpline at any of Barrick’s mine sites in 2020.

A mine surveillance tower looks over residential areas ©2022 RAID

(f) Problems with reliance on third-party assessments of the human rights situation at the mine

Barrick’s public-facing materials cite assessments by the consultancies Avanzar LLC and Synergy Global to support its claims of adequate and/or improved management of security and human rights issues at the North Mara mine. Problems with companies relying on assessments or audits that are not transparent and that they commission or that are otherwise not fully independent to establish their human rights credentials are well known.

In this case, Barrick has not demonstrated that the assessments were independent. Avanzar has been hired by Barrick for assessments at Barrick’s various mine sites, beginning in 2011, and in North Mara has also been retained to conduct training programs. It thus has a longstanding financial interest in its commercial relationship with Barrick. Synergy was hired to conduct assessments by MMTC-PAMP, the North Mara mine’s refiner since at least 2013, which also has a longstanding financial interest in its commercial relationship with Barrick. Its Terms of Reference were “established in collaboration” with Barrick (and have not been disclosed), and the assessments are under a programme run by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), which controls access to the world’s largest gold market and shares board members with Barrick and MMTC-PAMP. MMTC-PAMP states that the assessment was independent.

Further, the assessments are not transparent, preventing external scrutiny or evaluation. None of the assessments by Avanzar or Synergy have been published in full, or even in significant part. The most that has been published for any of them is an executive summary of Synergy’s first assessment, which was based on a short site visit to North Mara during which Barrick had control over those with whom the assessor met. RAID has previously published in detail its concerns with Synergy’s first assessment, based on the Executive Summary and its engagement with Synergy, the LBMA and MMTC-PAMP during the process.

In its communication with RAID, Barrick said that “independent auditors who have undertaken thorough investigations” at the mine since November 2019 “have publicly commented on the considerable improvement that has occurred with…security matters at the mine since Barrick took over operational control.” RAID is unaware of any public comments of that nature by an auditor or assessor. RAID requested Barrick to identify where such public comments may be found. Barrick did not do so.

RAID also requested that Barrick publish the full assessments by Avanzar and Synergy so that they may be available to local communities and subject to public scrutiny. Despite saying that Synergy’s follow-up assessment “revealed significant improvements in managing security and human rights related risks at the mine site”, Barrick has still not published these.

In its communication with RAID, Barrick also said that “local and national human rights and civil society organizations” were invited “to undertake independent assessments at the Mine” (it also relied on this invitation in its latest report to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights). RAID spoke with several of these organisations after their visit. They said that they did not consider their visit to the mine as constituting an independent assessment, and expressed concern that Barrick may be characterising their engagement in such terms. The visit involved presentations from mine personnel and a single meeting, held on the mine site, with village representatives selected by Barrick.

Key Recommendations

- Barrick should urgently consider ending the mine’s relationship with the police.

- Barrick’s board should establish a truly credible, transparent and independent investigation into the killings, assaults and other human rights abuses at the North Mara mine.

- Barrick should implement an appropriate grievance mechanism and take the steps necessary to ensure that remedy is available and meaningfully accessible to those who have been seriously harmed by its operations.

Riding along the mine wall from Kwimange to Nyangoto, North Mara, Tanzania ©2022 RAID