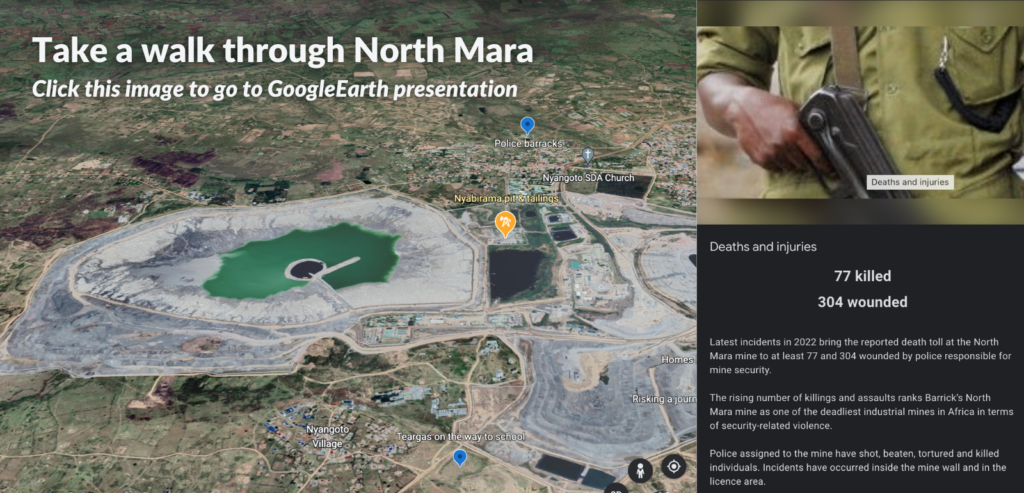

Violence against Indigenous residents intensifies with rising numbers of killings, assaults and torture by police assigned to the North Mara mine, bringing the death toll to at least 77 and 304 wounded

Download full press briefing here.

Attacks on Indigenous Kurya residents have intensified at Barrick Gold’s North Mara mine in Tanzania, according to new research by UK corporate watchdog RAID. Since the Canadian mining giant assumed operational control of the mine from its subsidiary Acacia Mining in September 2019, violence by police in mine-related security operations has led to 32 recorded shootings, incidents of torture and other assaults, resulting in six deaths.

Breaking these cases down, RAID’s latest research, conducted between April and October 2022, has documented two people killed and 18 injured since the start of 2022 alone. This is in addition to four people killed and eight more seriously injured by police in the preceding two years, all but one of which RAID previously reported on.

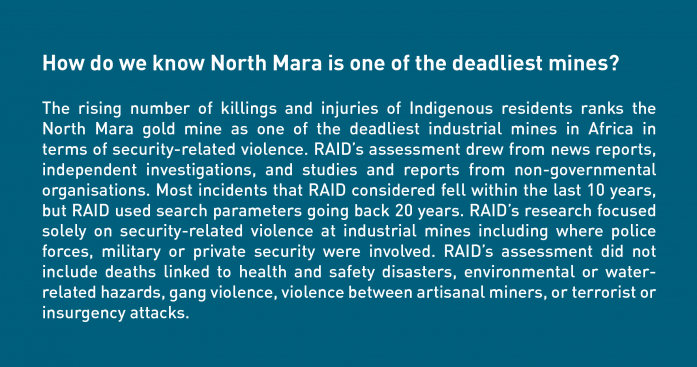

These latest incidents bring the reported death toll at the North Mara mine to at least 77 and 304 wounded by police responsible for mine security, most of which occurred after Barrick acquired the mine in 2006. The rising number of killings and assaults ranks Barrick’s North Mara mine as one of the deadliest industrial mines in Africa in terms of security-related violence.

“Barrick Gold may promote grandiose ESG claims about its operations at the North Mara mine, but the appalling death toll of Indigenous residents speaks for itself,” said Anneke Van Woudenberg, Executive Director, corporate watchdog, RAID. “Barrick Gold cannot hide from the stark fact that it is operating one of the deadliest mines in Africa. Without an end to the abuses and justice for those harmed, shareholders and pension funds invested in Barrick should think twice about whether this is a company they can continue to support.”

Leaders of the surrounding Kurya villages, whose people have long engaged in farming, cattle-herding and artisanal mining in the area, say the mine has taken their land and increasingly encroached on their way of life. Leaders and residents interviewed by RAID said that the mine’s arrival has led to Kurya community members being treated as “invaders”, targeted and criminalised.

RAID sought Barrick’s response to reports of the latest incidents. On 14 July 2022, Barrick stated that “we do not tolerate human rights violations” and that these were “extremely serious allegations” warranting “a thorough investigation conducted with the utmost care and meticulousness”. It further stated that it would respond to the allegations once its investigation was completed. To date, no further information has been received from Barrick.

Increased violence and torture

Community members say the violence against them has increased over the past 12 months. They say “mine police” (a term used by local residents to refer to police the mine engages to provide security) regularly conduct mine-related operations in residential areas, force their way into homes without a warrant, arbitrarily arrest and beat residents, and fire teargas and ammunition indiscriminately, including near children.

In what may be a new tactic, RAID also found that these police tortured Kurya residents in mine-related operations to, among other things, extract confessions that they had trespassed onto the mine or been involved in theft from the mine, or force them to identify others allegedly involved in such activities. In at least two instances, RAID found indications that mine personnel may have been aware of the torture.

Artisanal mining, Nyabichune village, near the waste rock pile of Nyabirama pit at the North Mara mine ©2021 RAID

In one case in or around August 2022, Mwita (not his real name) was detained by “mine police” after they shot him in both legs with teargas cannisters from close range as he was leaving a local village centre. The police took him to an area by the mine wall where he was positioned in front of one of the mine’s CCTV cameras, which are monitored by the mine’s control room. The police compelled him to look directly at the camera, which swivelled to face him. Mwita heard the police communicating over their radio, asking if they had apprehended the right person. The voice over the radio, which Mwita understood was from the person watching the CCTV camera, said no, but told the police to ask Mwita the whereabouts of the people they were looking for. Mwita told the police he did not know.

The police took Mwita to a mine vehicle stationed below the CCTV camera, where his hands were fastened behind his back and he was affixed to a rod, faced downward and repeatedly beaten with a club. During the beating, Mwita again heard the voice over the radio, asking the police if Mwita had told them anything yet. The police replied that he had not, and the beating resumed. When he was eventually released, he said, “I couldn’t walk properly” due to the pain and injuries he had incurred, but he was forced to make his own way home. Before releasing him, the police told him to tell others what had happened to him, so they would be aware of the consequences if they tried to enter the mine.

In another case in or around April 2022, John (not his real name) was arrested in a local shopping area and accused of being involved in theft from the mine. Although the “mine police” searched his home, they found nothing, and returned him to the police station. At the station, he was ordered to confess to going to the mine, or they would “crucify” him. John said that they repeatedly tortured him, including by suspending him from a rod and beating him with batons.

Those interviewed by RAID in recent months describe a growing climate of fear, and said that speaking out about the violence and other human rights abuses linked to the mine was understood to be dangerous. In a public meeting convened in or around April of this year, a senior police representative told those gathered, in the presence of mine officials, that “anybody who goes to the mine will be shot”.

Daily life continues along the mine road separating the North Mara mine wall from homes in Nyabikondo village, near the site of one of the recent shootings ©2022 RAID

Barrick’s changes to security strategy

The intensification of violence coincides with the expansion of the mine’s concession area and Barrick’s replacement of the mine’s internal security team with a new security provider, Nguvu Moja, in late 2020. Barrick removed weapons, including “soft options”, from Nguvu Moja guards which, according to former mine security personnel interviewed by RAID, would mean an expanded role for the police in the mine’s security operations, and thus an increase in violence. According to local leaders, Barrick’s extensive use of the police, rather than private security, seeks to minimise the company’s legal liability for violence against local residents.

The North Mara mine pays, equips, feeds and houses on an ongoing basis roughly 150 police officers, who operate under a signed agreement between the company and police. They are armed with rifles, submachine guns, batons and wooden clubs, as well as teargas and sound bombs that they fire from launchers. In correspondence with RAID, Barrick says that the mine does not employ, “supervise, direct or control” police assigned to it, and is not responsible for their conduct, and that references to “mine police” are “factually incorrect”.

But members of the mine’s internal security team and police officers interviewed by RAID say the police assigned to the mine form part of the mine’s security structure. They say the police are deployed to specific areas around the mine site, that they are present in the mine’s security control room, and that they use the same radio frequency as the mine’s internal security team. A senior police commissioner confirmed to RAID in May 2022 that police engaged by the mine provide their services to the mine exclusively and not to the community at large.

Barrick’s response and claims of improvement

Barrick says that since taking back operational control in 2019 from its subsidiary Acacia Mining, it has “radically repaired” community relations and established “clear boundaries” with local police. RAID’s findings contradict these claims, as well as the suggestion in Barrick’s reporting that there has been a “[r]eduction in use of force” in mine security operations.

RAID will formally submit information concerning the most recent human rights violations as part of its complaint to the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), which since 2014 has certified gold mined from North Mara as being “responsibly sourced”. This certification means that North Mara gold may enter the supply chains of some of the world’s largest companies including Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Tesla.

The LBMA recently confirmed that MMTC-PAMP, the Indian refiner that processes gold from the North Mara mine, remains on its Good Delivery List. The trade in gold continues despite an assessment commissioned by the refiner that ranks risks concerning “security forces management and potential human rights abuses” as “high” (see below).

For more information, please see:

- Barrick’s response and full correspondence with RAID here and Barricks’ 14 November 2022 response to this RAID briefing here.

- RAID’s March 2022 briefing on police violence at the North Mara mine, Barrick’s statement in response, and RAID’s rebuttal

- RAID’s March 2022 complaint to the London Bullion Market Association

- RAID’s press release on the UK legal action against Barrick subsidiaries, and addition of claims

Motorcycle approaches crossing with North Mara mine road in Nyangoto village ©2021 RAID

North Mara Gold Mine:

One of the deadliest mines in Africa

RAID’s research

RAID has conducted numerous research missions to North Mara, beginning in 2014. Since Barrick assumed operational control of the mine in 2019, RAID has completed nine research missions and carried out over 178 interviews in person and by phone, including with those injured, witnesses, family members, village leaders, local authorities, elected officials, former mine employees, security personnel, and members of the Tanzania Police Force. Nearly all of the interviews were individual, and most lasted for more than an hour.

RAID published a briefing in March 2022 reporting that at least four people had been killed and seven more seriously injured by police engaged by the mine between December 2019 and December 2021.

Between April and October 2022, RAID completed three more research visits to North Mara, and documented a further two incidents in which people were killed and 19 more in which they were injured by police in mine-related security operations since December 2019. Of these, both of the deaths and 18 of the injuries occurred since January 2022. It is the 2022 period on which this report is focused, which should be read as an extension of RAID’s March 2022 briefing.

Nearly all of those interviewed by RAID spoke on condition of anonymity due to concerns for their safety or circumstances of employment, which RAID assessed were reasonably held. Accordingly, all names have been changed and care has been taken to protect identities.

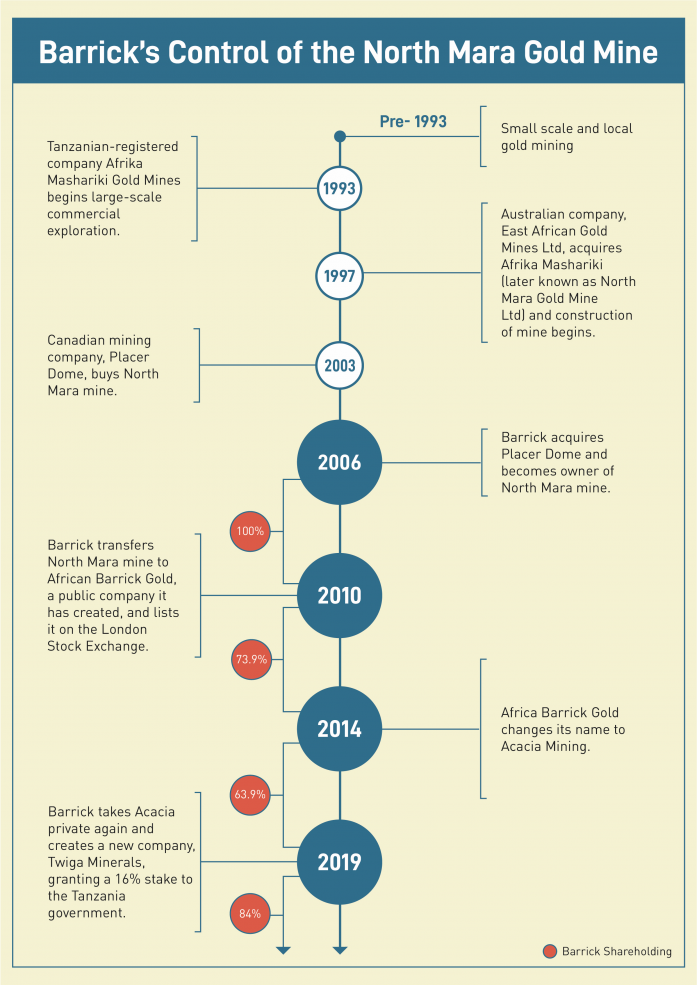

Barrick’s ownership of the North Mara mine

Barrick is the world’s second largest gold mining company with revenue of nearly $12 billion in 2021, and nearly $6 billion in the first half of 2022. Barrick is incorporated and headquartered in Canada and is a publicly traded company listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). It plans to include the North Mara mine in northern Tanzania in its elite “tier one” portfolio.

Homes in Nyabichune village against backdrop of waste rock pile by North Mara mine’s Nyabirama pit, where Kurya residents say they face ongoing pollution of dust from the mine ©2022 RAID

The North Mara mine began commercial production in 2002. Barrick acquired the mine in 2006, which it owned through its local subsidiary, North Mara Gold Mine Limited. From 2010, the mine was operated by Barrick’s subsidiary, African Barrick Gold, which it listed on the London Stock Exchange, retaining a controlling financial interest. In 2014, African Barrick Gold was renamed Acacia Mining. In September 2019, Barrick bought out Acacia Mining’s minority shareholders, delisted it, and took it back in-house. Barrick now operates its Tanzanian mines, including North Mara, through a newly formed company, Twiga Minerals, in which the Tanzanian government holds a 16% stake.

Throughout these changes, Barrick’s shareholding has not fallen below 63.9% and it was more often higher.

One of the deadliest mines in Africa

The latest incidents that RAID has documented follow over a decade of reports of serious human rights violations at the North Mara mine. There have been credible reports of at least 77 people killed and 304 people injured, many on multiple occasions, by police responsible for mine security, most of which occurred since Barrick acquired the mine in 2006. These figures include the reports received in person by a Tanzania Parliamentary inquiry in 2016. Local leaders involved in that inquiry told RAID they believed this was an underestimate.

The Kurya people and the North Mara mine

The Kurya (sometimes spelled ‘Kuria’) people are indigenous to an area of east Africa that spans the Tanzania-Kenya border. They are the majority ethnic group in the Tarime district, where the North Mara mine is located, in northern Tanzania’s Mara region. For generations, small-scale mining and agro-pastoralism have been mainstays of the economy for the area’s Kurya communities, their customary land tenure system an important source of natural resource management.

Areas for Kurya residents to graze cattle, seen here in Nyabichune village in front of waste rock by the North Mara mine’s Nyabirama pit, have shrunk as the mine has expanded ©2021 RAID

In the early 1990s, Afrika Mashariki Gold Mines, which in 1997 was taken over by Australian company East African Gold Mines, began exploring the prospects for a large-scale industrial mine, which became the North Mara mine, in an area in the Tarime district with seven established Kurya villages. According to a former chairperson of one of those villages, interviewed by RAID in January 2022, “When the mine came, it did not do research and get its own area to start mining. It took the area that was already being mined by locals.”

The mine’s land acquisition process impacted many households. The former chairperson added, “People didn’t know a lot about the value of their land. They were just presented with what they were paid, and they had to accept.”

Those who did not accept faced the risk of being forcibly evicted. According to a detailed complaint in 2003 by the Lawyer’s Environmental Action Team (LEAT) in Tanzania to the state’s Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance, many such evictions were carried out by members of the Tanzanian Police Force to clear the way for the mine’s development. A Kurya elder who was an elected official at the time told RAID:

“They evaluated the land, but when people were called to get their payment, they were subjected to receiving only pennies, so they refused… For those who refused, they got beaten up really badly [by the police].”

Prior to the mine’s arrival, there had been very limited police presence in the area. The mine’s development brought a significant increase in that presence, and with it an increase in violence and human rights violations that continue to this day (see below).

a) Commencement of the mine’s operations

The mine began commercial operations in 2002. Today it comprises two adjacent pits, Gokona (underground) and Nyabigena (recommencing operations this year), and a third, Nyabirama (open pit), which is connected to the others by a mine road that cuts through local villages.

To understand the problems associated with the mine, including the killings, a Kurya human rights defender told RAID, “you must understand the land issues”. The mine was constructed in the midst of the existing Kurya villages, and the land it has claimed extends well into residential areas, with sizeable white boulders interspersed throughout villages marking the mine’s property claims.

Large white boulders positioned next to homes in Nyangoto village mark the North Mara mine’s property claims ©2021 RAID

In some areas, the mine wall is separated from homes by only a dirt road. According to local leaders interviewed by RAID, the mine has failed to provide for a 200-metre buffer zone between its perimeter and local homes, which they said was inconsistent with Tanzanian law.

According to local leaders and Kurya residents, this close proximity between traditional residential areas and the mine has long been the source of problems, exposing residents to pollution and other environmental harm, and the effects of blasting at the mine, as well as limiting their ability to develop their land.

The mine’s development has also dramatically affected livelihoods, cutting off Kurya residents from areas where they had traditionally conducted artisanal mining and farming. A Kurya resident with a local leadership position told RAID in July 2022:

“[Our] people rely on gold but the thing is, people have nowhere to go to access rocks because the mine has expanded so extensively. It has taken a vast area, displacing people and then expecting people to survive.”

(b) Ongoing expansion of the mine

Under Barrick’s operational control, the mine’s expansion has continued as it seeks new areas to exploit gold. Again, this is displacing communities. In January 2022, a former village chairperson told RAID that such displacement is an issue of ongoing and significant concern:

“The little compensation from the mine is causing poverty, it is bringing people down. They are giving up land that is way more valuable than what they are getting, and it is making people poorer… People are being removed now, and we don’t know what will be happening to them. I don’t know why the government won’t defend its people. It is much more in favour of the mine than the people, but it is the people who own the land.”

According to the former chairperson, the land acquisition process has led to a significant deterioration of conditions for the Kurya people in the area:

“It’s really bad, and I think it’s going to have a really bad impact in the near future. A lot of people don’t have the knowledge to make a living from other [income] sources, because they have always depended on mining. But now their land is taken, and even farming areas are scarce for them. It is a major challenge.

The biggest impact that it will have is for the children. They also suffer, because when their parents suffer, children suffer as well.

The taking of land without compensation makes people poor, and when people become poor, they become hungry, literally hungry, and they become desperate, and this is why ‘intruders’ keep going [to the mine] and won’t stop. When people are hungry, they need to feed themselves and so they revert to intruding to try to ensure that they can eat.”

A Kurya resident with a village leadership position told RAID in July 2022 that his community has tried to resist the mine’s harmful impacts. At a meeting in or around April 2022 attended by mine officials, village authorities and the police, community members explained they had few options to feed their families other than going to the mine:

“People asked how could they survive? Farming is not enough and they don’t know how to do anything else but mining. What are they expecting us to do? Go rob people’s shops to get something to feed our families? People were saying to [mine officials and the authorities], ‘We live here, we see the mine, we see the rocks, and we need to feed our families. We would rather go to the mine than rob people, so even if we are shot for going to the mine, we will keep going.’”

RAID sought Barrick’s response to reports that as part of its expansion, residents were being forced to relocate without adequate compensation and without another property or home to move to, which was inconsistent with the standards by which Barrick says it is “guided”. The company did not respond. In 2020, Barrick said most of the “outstanding land claims at North Mara have been settled”, though without providing details. The Kurya human rights defender disputed Barrick’s claim to have settled most of the land claims when RAID interviewed him in November 2021.

Artisanal mining, often a joint venture amongst Kurya community members, in Nyabichune village by the North Mara mine ©2021 RAID

(c) Accessing waste rock as a strategy for survival

One of the ways people have sought to survive is by collecting gold-bearing material from waste rock areas where the mine dumps rocks that contain too little gold for it to be sufficiently profitable for the mine to process. In previous years, local residents were permitted to access such areas to try to find small amounts of gold amongst the waste rock, but RAID is told that this is no longer the case under Barrick’s operational control. A Kurya man from Matongo, one of the surrounding villages, told RAID in August 2022:

“The relationship between communities and the mine is not good at all… Before, at least the mine used to dump waste rocks for people and we could go and get something. But now, that doesn’t happen anymore. That’s why people can’t stop going, because many people depend on gold bearing rocks. It’s not like people go to the white man’s house to steal, they just go to get waste rocks.”

RAID was told that people asked the mine to designate an area where it would place waste rock that local residents could safely access and that they raised the issue in community meetings with the mine. Barrick told RAID that it did not plan to do so, including because in its view it would not be considered sustainable.

Even if it is no longer permitted, local residents say they have no option but to continue to try to access the waste rock because the mine has taken areas on which people had previously depended for income. “You have a family, you have kids,” one Kurya man from Nyabichune, another of the surrounding villages, explained in June 2022. “If there is waste material, that is where you at least have a chance to feed your family.”

Police assigned to the mine appear to be using the need of those from the surrounding villages for access to waste rock areas to elicit bribes for access. In some cases, RAID found evidence that police specifically targeted individuals who did not pay them or who refused to give them a portion of the gold they had found. For more on the security problems posed by the police, and views of former members of the mine’s security team regarding the involvement in unlawful conduct of police engaged by the mine, see RAID’s March 2022 briefing.

Police violence at North Mara

The unlawful use of force by Tanzanian police officers engaged by the mine to provide security has long been central to the human rights problems at North Mara. These officers, referred to as “mine police” by local residents, are assigned to the mine, generally rotated through for a period of between six weeks and three months, and mostly brought in from outside the area. Since at least 2008, this arrangement has been formalised through Memoranda of Understanding between the mine and police.

As noted above, under these Memoranda, the mine equips, feeds and accommodates in barracks built by the mine approximately 150 officers on an ongoing basis. It also pays each officer a daily sum in addition to their regular salary, making it a particularly lucrative posting. The mine further provides benefits to senior officers in the Mara region including monetary payments, vehicles, vehicle maintenance, fuel and accommodation within the mine.

Green-roofed barracks provided by North Mara mine for mine-assigned police, Nyangoto village in the background ©2021 RAID

In respect of each of the cases documented, those RAID interviewed identified “mine police” as being involved, including because: (i) of where the police had been posted (for instance, by the mine wall); (ii) they had been in mine vehicles, identifiable, for example, by their license plate, colour, make and wire-mesh-covered windows; (iii) they were in, or had emerged from, the mine site during a security operation; and/or (iv) they were communicating by radio with the mine control room, including being directed over radio while being tracked by mine security cameras.

Local leaders and residents interviewed by RAID are clear that the “mine police” are not the same police as those carrying out routine, day-to-day policing activities relating to community issues in the area.

(a) Integration of the police within mine security operations

As noted above, according to members of the mine’s security team and police officers interviewed by RAID, the police officers engaged by the mine are integrated within, and are a key part of, the mine’s security operations. For more on the police’s integration, see RAID’s March 2022 briefing.

After Barrick took over operational control of the mine, its President and CEO, Mark Bristow, said that “the police are there to maintain community peace and law and order and we are part of that community”. However, police officers, local residents and village leaders say that police guarding the mine provide their services to the mine exclusively and not to the community at large.

When RAID met the Tanzania Police Force’s Commissioner of Operations and Training in May 2022, he confirmed that the police engaged by the mine under the applicable Memorandum of Understanding are there solely to “safeguard” the mine and “are just there to protect the investor, that is all”. He further explained that without the mine’s support, “we would just do regular patrols. If, as police, we go to do special work for an investor, you must pay a little, otherwise we will not do it.”

Barrick did not respond to questions concerning its relationship with the police in relation to the most recent incidents. However, in response to RAID’s March 2022 briefing, Barrick stated that “[t]he North Mara Gold Mine does not manage or control an independent police force”, the “Tanzania Police operates under its own hierarchical chain of command and makes its own policing decisions”, and “[p]rivate companies such as North Mara Gold Mine Limited are not expected to monitor or report on day-to-day police activities outside of the mine”. RAID addressed these assertions in its March briefing and in its rebuttal to Barrick’s statement.

When Barrick’s position was put to Neema (not her real name), a Kurya woman whose son was recently killed by police guarding the mine, she rejected Barrick’s attempt to disclaim responsibility, telling RAID in May 2022:

“It starts with the company. Let me explain. If you are hiring people, don’t you have the power to tell them not to kill someone? And if they do kill someone, don’t you have the power to fire them? So that is why it starts with the company, they are paying the police who do these things. The white man has the power… to prevent these things from happening, but chooses not to.”

Mine vehicle used by police deployed at Barrick’s North Mara gold mine ©2022 RAID

(b) Lack of accountability for police violence and other misconduct

To RAID’s knowledge, no police officer has ever been disciplined for the use of excessive force at the mine, though it has sought responses from both Barrick and the police on this question. In the meeting with RAID this year, the Tanzanian Police Commissioner of Operations and Training said that the mine had not raised any allegations of misconduct or excessive force by the police and that he would have been aware had it done so.

The Police Commissioner emphasised that police officers are entitled to protect themselves and that they often encounter people throwing stones, though he said that he had never heard of those going to the mine bringing a firearm. Asked if he was aware of complaints by local residents about police violence at the mine, the Police Commissioner replied that, “[t]hese people cannot complain because they are criminals”.

Former security personnel confirmed to RAID that people entering the mine were not known to bring firearms, but that some caused injuries, including with stones and pangas (a machete-like agricultural tool). In their view, it was thus particularly important that the mine’s internal security personnel have “soft options”, such as foam baton rounds, in order to be able to respond appropriately. Thus equipped, they said, involvement of the police, who would often use disproportionate force, could be limited. As noted above, Barrick removed these “soft options” from internal security after taking operational control.

Intensification of violence

The cases documented by RAID that occurred since January 2022 follow a similar pattern to those previously reported. RAID did not find evidence establishing that the use of force by the police was justified in any of the cases documented. On the contrary, RAID found evidence indicating that the use of force was excessive and unjustified, and in many instances deployed as people fled or after they had been detained.

In all of the new cases documented, those injured or killed were identified as bystanders caught up in mine-related security operations, individuals targeted by police while in or leaving local villages for alleged mine-related wrongdoing, or individuals who were in or had fled the mine and its waste rock areas.

Police officer with mine vehicle, deployed across mine road by the North Mara mine’s Nyabirama pit wall ©2021 RAID

Twelve of the cases involved shootings, eight with bullets, including both deaths, and the others with a teargas cannister or other large projectile fired from launchers. In one of the shootings, the individual was shot twice with bullets, and in another, first with a projectile fired from a launcher and then with a bullet.

In one such case in or around July 2022, Samba (not his real name) said that he and others had gone to a waste rock area on the mine site. After a period of time searching for gold-bearing rocks, the police arrived. He and others fled, with the police giving chase. In addition to mine security vehicles carrying Nguvu Moja personnel, there were “a lot of policemen” driving mine vehicles. As he approached the mine wall, Samba recalled, “one of them fired and shot me in the leg”, which the bullet sliced through. He was still struggling to walk when RAID interviewed him in August.

In another case in or around February 2022, Daudi (not his real name) described a similar experience of going to a waste rock area with several colleagues when they encountered the police, one of whom shot him in the leg with a bullet as he fled. One of his colleagues, also interviewed by RAID, recalled:

“When we were running away towards the wall, [Daudi] was shot and said to me, ‘I’ve been hit’. I started pleading with the police to stop, I asked ‘why are you doing this, we are leaving.’… The police kept on coming, but we managed to get to the wall and were able to get over it.”

Another young man shot outside the mine during a mine security operation was still in hiding when RAID interviewed him earlier this year, several weeks after the incident. “The worry is that when the police catch someone, they can beat them up so bad they can cripple someone, or someone could even lose their life”, he explained. “And sometimes people will also get charged falsely.” His concerns are supported by other cases documented by RAID in which those detained by police guarding the mine suffered such treatment.

A more aggressive approach to security

As noted above, and covered in more detail in RAID’s March 2022 briefing, RAID’s research indicates that Barrick’s decision to appoint Nguvu Moja and then remove the (less lethal) weapons with which internal security had been equipped meant an expanded role for the police and increase in violence was foreseeable. This appears to be what has occurred: Kurya community members confirmed that police involvement in mine security operations, and violence against them, has since increased.

RAID’s research has found that the enhanced police role in the mine’s security coincides with the use of more aggressive tactics, a number of which are unlawful. These include the deliberate targeting and mistreatment of individuals, torture, detention in degrading conditions, the withholding of medical aid, and surveillance of those perceived as problematic for the mine in local communities.

North Mara mine surveillance tower with CCTV cameras rises above Nyabikondo village by the Nyabirama pit, as women search for gold-bearing material below ©2021 RAID

As part of these tactics, police engaged by the mine have expanded their security operations in the surrounding villages. These operations also appear to have greater involvement from an elite anti-terrorist unit within the Tanzanian police, known as the Crisis Response Team (CRT). RAID is unaware of any reports or concerns regarding terrorism in the area, nor did it find any evidence that the CRT is involved in anti-terrorist work as part of its deployment to North Mara.

(a) Deliberate targeting and use of torture

During the course of its recent research, RAID documented seven cases involving torture. Those interviewed described similar brutal tactics used by the police: they had their hands tied or handcuffed, held in place with an iron or wooden rod that pinned their arms either behind their back or under their knees, and were then beaten, generally with batons or clubs, often on their joints, palms or bottom of their feet. In some cases, the individuals were suspended in the air as they were beaten.

Peter (not his real name) said that he was in a public area near the mine when police arrived and detained him. He was driven to a nearby police station, where his hands were cuffed, and he was suspended from a rod. “They beat me so bad, hitting me on the joints, the knees, ankles, elbows” with a club, he said. During the beating, the police demanded to know where he was “selling his rocks”, referring to gold-bearing rocks that they were accusing Peter of taking from the mine. After the beating, he was put in a cell where he was held with others for many days. “I was in pain, my legs and arms were so swollen, but there was no medical attention,” he said.

In another case, Mhere (not his real name) described being detained in a local village by police and placed in a mine vehicle, before being driven within and around the wall encircling one of the mine’s pits. While in the vehicle, he said he was beaten and repeatedly electro-shocked with what appeared to be a taser as he was pinned on the vehicle floor. He recalled:

“I felt like every time they would do it, I would die. Every time, I was anticipating it, I was always scared if I could take that pain. You know, when you get shocked, you feel like the blood is getting sucked out of your body…. They were saying that I had to agree that I was at the mine and they would stop.”

At one point during this episode, while inside the mine walls, the vehicle stopped and Mhere was made to get up so that people wearing mine uniforms could inspect him.

In many cases, those tortured suffered significant injuries, and were subsequently held in degrading conditions, denied medical treatment and provided with limited or no access to food and water, in some cases for many days. One of those tortured and held in a cell at a police station by the barracks the mine provides for police assigned to it told RAID that while detained, he would occasionally be given leftovers if the police did not finish the food provided by the mine:

“The way the cell is, I could see outside. I could see the vehicle coming and we would know that food was here…. The company that supplies food to the mine is AKO, and you could see it written on the side of the vehicle. The food was coming for the police. We would only eat when they wouldn’t finish the food.”

RAID confirmed with a former driver for AKO, who explained that AKO is the catering company subcontracted by the mine, that he delivered food to the police daily. The driver told RAID, “We took them breakfast, lunch and dinner. The food was cooked in the mine. Barrick owns the kitchen. We take it straight from there to the police mess, or take food to other mine workers then to the police mess.”

As noted above and the cases described illustrate, in at least two instances involving targeting and torture of Kurya residents by the police in mine-related operations, there are indications that mine personnel may have been aware of the torture. In none of these cases did RAID find evidence that mine personnel took steps to ensure that those responsible were held to account or that medical care was provided.

(b) Increased intrusions into residential areas

The operations by police guarding the mine seeking to target suspected intruders and possibly others are increasing insecurity and human rights violations in residential areas, an issue identified in RAID’s March briefing. “There is a big difference with security now”, a Kurya man from Kewanja, one of the surrounding villages, told RAID in July 2022, “the mine police come to communities, even at night, and knock on people’s doors when they are sleeping and just arrest people.”

According to Kurya people from the surrounding villages, during these operations, police regularly fire live ammunition and teargas indiscriminately, including around children, break into homes without a warrant, damage property and conduct arbitrary beatings and arrests. Another Kurya man from Kewanja village interviewed by RAID in June 2022 described how police from the mine had recently broken the door of his family home and arrested him and his brother, without showing them a warrant, and accused them of going to the mine. He told RAID:

“there is always mine police going to the communities. Sometimes the police use vehicles that spray itchy water and kids get affected. People who have done nothing wrong get caught up with what police do…. we just live around this area, but we have no peace.”

Neema (not her real name), whose son was recently killed by police guarding the mine, told RAID in May 2022:

“We warn our kids not to engage with the police. We tell them to pass somewhere else if they see them…. Given what goes on around here you worry everyday if your children will come back home alive when they leave for school.”

She explained to RAID that the firing of teargas by those she referred to as mine police is an ongoing issue that affects children particularly:

“Sometimes the [teargas] smoke will enter the home and babies suffer a lot, you will find them crying, and they cannot protect themselves.

What are they doing to this generation?”

Children on their way home from school by the North Mara mine’s Nyabirama pit wall, Nyabichune village ©2021 RAID

(c) Increased involvement of the Crisis Response Team

As RAID reported in its March briefing, the police engaged by the mine on an ongoing basis include members of the Field Force Unit (FFU), a special division within the police force responsible for riot control. According to former mine security personnel, even prior to Barrick assuming operational control of the mine, they also included members of the Crisis Response Team (CRT), a “S.W.A.T.-style” police unit, armed and trained by the US government, that was formed in 2014 to address terrorism threats. Those from surrounding villages and former mine security personnel described members of the CRT as being particularly “aggressive”. As one resident said, “[t]hey don’t laugh with people” but “just start firing”. Another told RAID, “[t]he CRT is very sharp and very involved, and very aggressive”.

Residents told RAID that it can be difficult to differentiate CRT and regular FFU officers, as they are similarly attired. However, in many of the recent cases documented, witnesses identified the police involved as being CRT and driving vehicles provided by the mine, which they described as white Land Cruisers that, unlike those provided by the mine to regular police officers, were open at the back, with piping and green canvas.

Mine vehicle used by police deployed on mine road by North Mara mine’s Nyabirama pit ©2021 RAID

When asked why they believed the officers to be from the CRT, witnesses said that this was how the officers identified themselves, or that they overheard mine personnel referring to them as CRT. For instance, one witness responded, “I know the CRT, that’s what they called themselves.” He also said that regular officers’ “uniforms have numbers to identify them. The CRTs go to the community with guns plus batons and handhoe handles [commonly used by police there as long wooden clubs] and don’t have numbers so that no one can report” them. Another told RAID that he could identify the CRT by the vehicle’s number plate.

Barrick did not respond to RAID’s question regarding services being provided to the mine by the CRT, but the frequency with which witnesses implicated them in the recent violence indicates that they are playing a more extensive role in mine security since Barrick assumed operational control.

Mine vehicle used by police, with police officers in the back, along the North Mara mine wall at Nyabirama pit ©2021

As a Kurya man from one of the surrounding villages explained to RAID, “[n]ow, it is all about the CRT. When something happens, the CRT goes there. When there is a certain issue, it is the CRT.” Another separately confirmed to RAID that “[t]he CRT are much more involved now in security,” and a third told RAID that now “the CRT is the one that the white man prioritises”. All of these interviews occurred in 2022.

Denial of and impeding medical treatment

As RAID has reported in relation to previous cases, contrary to international standards, those injured in the documented incidents occurring in 2022 were not provided necessary medical treatment “at the earliest possible moment” or at all. Further, the mine’s use of the police continued to impede injured individuals’ access to proper medical treatment, which in most instances they had to forgo or obtain covertly, including for injuries as serious as bullet wounds. For more on these issues, see RAID’s March 2022 briefing.

Threats against local communities and repression of freedom of expression

(a) Threats issued against local residents

At meetings convened in or around April 2022 in surrounding villages involving mine personnel, local residents told RAID that threats of violence were made against people entering the mine in search of gold-bearing material. The meetings included mine personnel, village leadership, and police officials, including the OCD (the commanding officer for the district). A Kurya man from Nyabichune village who attended one of these meetings recalled:

“We were told that anybody who goes to the mine will be shot because the government has a joint venture with the mine, so the mine is the government’s property…. The mine people seemed to be in line with what the police were saying. The [mine’s] security manager forbade people from going to the mine.”

Asked by RAID if anyone from the mine corrected the police or said that people were not to be shot if they went to the mine, he said that no one from the mine had done so. Another attendee, interviewed separately by RAID, said:

“I think they were trying to threaten people. They said if anyone entered the mine, they were going to get shot… It was a policeman who said that. There was pushback from village and hamlet chairmen who said that ‘no, you can’t do that’.”

When asked if mine personnel also objected, he said that they did not. All five of those from local villages who attended one of the meetings, each interviewed separately by RAID, confirmed that they understood the message to be a threat.

(b) Repression of freedom of expression and a climate of fear

RAID previously reported that since Barrick assumed control of the mine and partnered with the Tanzanian government, village leaders and residents have described an increasingly oppressive environment in which people fear speaking out against the mine. RAID’s more recent research indicates that this remains a serious concern. For instance, when asked earlier this year if people can speak out on issues concerning the mine, a leader from one of the surrounding villages told RAID:

“I don’t think people are free to speak critically about the mine. Where can you be free to criticise the mine? Where would be your platform? You can’t go anywhere to complain.”

The leader connected this problem with Barrick’s partnership with the Tanzanian government, explaining:

“Now the government has a stake in the company, so when something happens the mine just throws responsibility to the government. The government doesn’t want to be dragged to court, so it finds ways to hurt people more.”

Similarly, asked if she would be comfortable being identified in RAID’s report, a Kurya woman from Nyabichune village said no, explaining her reasons as follows:

“The white man is here for the gold. They are with the government. If they happen to know I am speaking and giving secrets about the mine, they might target me or my sons. It is really people from the government, the mine is where they eat from. Even the village chairmen, the sungu-sungu [community] guards, they get paid by the mine. And if they think I am putting those who benefit from the mine at risk, there is people’s hate.”

Some of those who were reportedly injured by police guarding the mine were not prepared to meet with RAID out of fear they might face reprisals should they speak about their experience. Accordingly, those incidents are not among the human rights violations referred to in this report.

Local and international human rights groups and institutions, including the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, have raised concerns that in recent years the Tanzanian government has overseen an increase in the repression of journalists, opposition party members and human rights defenders, and the closing of democratic and civic space. As part of that repression, human rights defenders, reporters and opposition politicians have been threatened, arbitrarily detained, violently attacked, abducted and disappeared. The Canadian government has also recently expressed particular concern regarding the human rights implications of restrictions on NGOs operating in Tanzania.

(c) Barrick’s response to concerns regarding threats and repression of freedom of expression

In correspondence, RAID sought Barrick’s response to concerns about the repression of freedom of expression and the meetings at which threats were reported. Barrick says that it does “not tolerate threats, intimidation, or attacks against human rights defenders.”

In its response, Barrick did not address these concerns or threats, but instead attached what the company described as a “confirmation statement”, dated 13 July 2022, and signed by 22 local leaders. The statement said that, “NMGM [North Mara Gold Mine] strongly observes and upholds principles of human rights and dignity” and that RAID’s reports of human rights abuses were “false”, and urged authorities to take action against RAID, referencing legislation that the Canadian government had identified as cause for concern.

According to Barrick, at a meeting it held with local leaders three days before the statement was signed, “astonishingly” none of the leaders said they knew of RAID, nor did any of them corroborate the concerns or allegations of human rights violations. Barrick says the ruling party’s local Member of Parliament, the Hon. Mwita Waitara, also attended the meeting.

In fact, RAID regularly consults with local leadership, although since Barrick assumed operational control of the mine, RAID has found that fewer local leaders are willing to meet to discuss human rights issues, and those who have agreed to such meetings have done so on condition that they are confidential.

RAID advised Barrick of letters addressed to the mine, officially stamped by the same village authorities whose representatives signed the “confirmation statement”, which specifically reference violence by police guarding the mine. MP Mwita Waitara also features in a publicly-posted video speaking at a funeral of a young man, whom he says the police killed. MP Waitara relates the young man’s death, which he says was intentionally caused, to the broader issue of police violence at and around the mine, stating that, unlike at other mine sites in Tanzania, young people living in the area are getting killed.

Finally, RAID noted that the “confirmation statement” underscores concerns expressed by Kurya residents and village leaders about speaking freely. The UN Declaration on human rights defenders provides for the right to unhindered access to, and communication with, non-governmental organisations for the protection of human rights. In response, Barrick said that RAID was attempting to “discredit the local leaders”, but has not addressed the concerns regarding repression of freedom of expression or threats.

Public road divides Muruambe hamlet of Kewanja village and the North Mara mine’s Gokona pit ©2021 RAID

Absence of remedy and impediments to justice

Barrick states publicly that it seeks “to facilitate access to remedy” and that it has a grievance mechanism at North Mara that received 10 grievances in 2021. However, local residents have consistently told RAID that they are unaware of any grievance mechanism at the mine, and none of those injured or those whose family member was killed has received remedy, though several told RAID that individuals had communicated with the mine about their cases.

RAID raised these issues previously with Barrick, but although Barrick stated it worked to ensure a community grievance mechanism “is accessible to all community members”, it provided no details as to how RAID or local residents could find more information about the mechanism.

For more on the absence of remedy at the North Mara mine, see RAID’s March 2022 briefing.

In cases that arose prior to Barrick’s assumption of operational control in 2019, the lack of remedy or justice led local residents to pursue claims for killings and assaults at the mine in the UK, where Barrick’s subsidiary, Acacia Mining, was incorporated.

Transnational legal actions for violence at North Mara

In 2013, Tanzanian residents brought a legal case to the UK courts for killings and assaults by security forces at the North Mara mine. Acacia Mining settled the legal action in 2015.

In 2020, another UK legal action was initiated by Tanzanian residents for ongoing killings and assaults between 2014 and September 2019. The action includes claims concerning a nine-year-old girl who was killed by a mine vehicle driven by police, and four women who were fired upon while gathering around her body. In 2022, a UK court order obliged Barrick’s subsidiaries to review up to approximately 100,000 documents for disclosure related to its security operations and human rights abuses at the mine. The case is ongoing, and Barrick’s subsidiaries deny liability.

RAID’s complaint to the LBMA

As noted above, since 2014, gold from the North Mara mine has been certified as “responsibly sourced” by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), which describes itself as “the independent precious metals authority”. That certification assures gold produced by the mine can enter the supply chains of many of the world’s major companies, including Apple, Amazon, Tesla, Alphabet and Microsoft.

In March 2022, on the basis of the killings and assaults detailed in its briefing of that month, RAID submitted a complaint under the LBMA’s Incident Review Process. In July 2022, the LBMA issued the North Mara mine’s refiner, MMTC-PAMP, part of the Swiss-based MKS PAMP Group, another Responsible Sourcing Certificate. On 4 November 2022, the LBMA issued a statement confirming that MMTC-PAMP remained on its Good Delivery List. Citing an assessment commissioned by MMTC-PAMP, the LBMA said that it “recognises the progress that has been made in relation to the North Mara Gold Mine”. RAID has received no information from the LBMA as to how this decision was made, nor the status of its complaint.

In a corresponding statement, MMTC-PAMP said that an “independent assessment” by its appointed consultancy, Synergy Global, “confirmed MMTC-PAMP’s decision to continue to source from the mine.” It said that the assessment “concludes that there were additional measurable improvements in the managements [sic] of risks” at the mine.

MMTC-PAMP published a short executive summary of the assessment, dated 12 September 2022 and based on a five-day site assessment visit to the mine in February 2022. The summary states that “[n]o part of this document may be reproduced without the prior written approval of” not just Synergy but Barrick, with which the site assessment was coordinated and which reviewed the report prior to finalisation. The full assessment has not been made public, nor have its Terms of Reference despite requests by RAID.

The executive summary refers to “measurable improvement in the management of the risks” and recommends continued trading with the mine. Yet it also states that “the potential significant adverse risks remain high, relating to security forces management, land issues and grievance management”, noting “ongoing alleged incidents of fatalities and serious injuries linked to public security forces managing…illegal intrusions”. More concerning still, it states that “it is not necessarily expected that all agreed actions can be completed within a defined period of time, nor that it is possible to demonstrate elimination (or significant reduction) in these risks within the period”. The implication of this statement appears to be that it is expected that the mine’s ongoing operations may lead to further killings, torture and other serious human rights violations against Kurya residents, and that this need not prevent Barrick’s business partners from continuing to trade with it, nor the LBMA from continuing to certify the gold produced by the North Mara mine.

The executive summary provides little support for its conclusion that the mine has “made significant measurable progress managing security and human rights”. It states that this progress has related particularly to private security, noting that the mine has contracted a Tanzanian company (Nguvu Moja), which is not armed and takes a “non-confrontational approach”. As detailed above, however, Barrick’s decision to appoint and disarm Nguvu Moja guards has coincided with a predictably enhanced role for the police in mine-related security operations, and an intensification in violence.

The executive summary does not address the question of whether there has been a change in the level or nature of security-related violence, which is a significant omission for an assessment purporting to measure improvements in security management and human rights. Rather, the executive summary identifies steps that it says have “contributed to a significant reduction in the number of arrests of intruders, despite the increase in attempted intrusions”. It is unclear how this measure indicates improved security management, particularly when accompanied by evidence of intensifying violence. This is especially so when much of that violence is inflicted on those who could simply be arrested if they were indeed engaged in illegal activities.

Recommendations

Read here the steps that RAID has urged Barrick to take to address the ongoing violence by police engaged by the North Mara mine.